What is a mini gastric bypass?

The Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB), also called the One-Anastomosis Gastric Bypass or Omega Loop Gastric Bypass, is a variant of the Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) that is less invasive and takes less time to perform. The MGB is preferred by many because of its efficiency and lack of side effects.

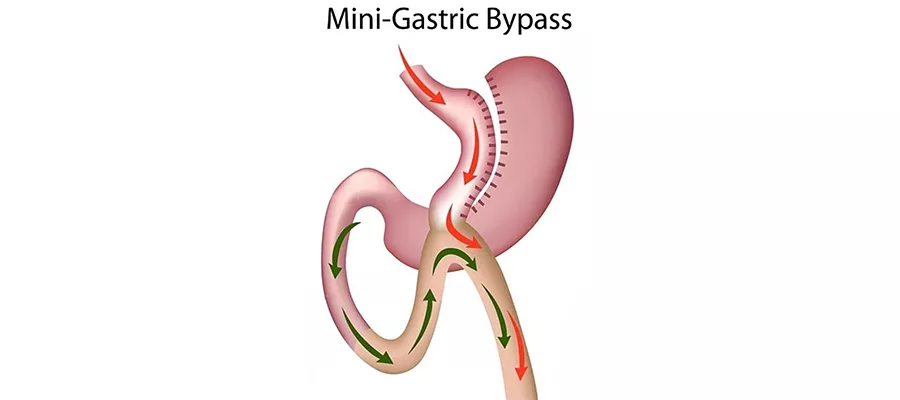

A long and narrow pouch is created by stapling a considerable part of the stomach together, just as in the conventional RYGB. In MGB, however, the pouch is tubular rather than compact and circular as in the conventional approach.

By connecting the newly formed stomach pouch (through anastomosis) to a loop of small intestine, a large section of the small intestine is avoided. The length of the skipped section might change depending on the specifics of the procedure (such as the level of malabsorption being sought)

The MGB surgery is less complex than the RYGB because it requires fewer anastomoses, or surgical connections.

Studies have proven that the MGB is just as effective as the conventional RYGB in helping people shed unwanted pounds.

Reduction or Elimination of Obesity-Related Comorbidities: Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnea are all disorders that may respond well to MGB, as they do to other bariatric procedures.

Any bariatric operation reversal would be complicated, although the procedure is reversible in principle.

Bile reflux occurs in certain people and may increase the likelihood of stomach and esophageal problems.

Malnutrition: Since the surgery induces malabsorption, nutritional deficits are possible, and may be more severe than with a conventional RYGB.

While numerous studies have looked at the impacts and consequences of standard RYGB over time, research into the MGB is still in its infancy.

Is a mini gastric bypass better?

The MGB is less compliated surgically and often has a shorter operation duration than the RYGB. This may imply less time spent unconscious and fewer risks connected with prolonged surgical procedures.

Some research suggests that, compared to RYGB, MGB may provide the same or higher amount of weight reduction.

While the RYGB requires two anastomoses (surgical connections) between the stomach and intestine, the MGB just requires one. Internal hernias and similar problems may be less likely to occur as a result.

While the logistics of undoing anything are complicated, the MGB is theoretically reversible.

Mini gastric bypass (MGB) risks and issues:

The risk of bile reflux into the stomach is a major issue with the MGB but seldom occurs with the RYGB. Damage to the gastric lining from bile reflux may lead to ulcers and even cancer of the stomach lining if left untreated.

Since the MGB skips through part of the small intestine, there’s a chance that certain nutrients won’t be absorbed. This is also a possibility with RYGB, albeit the degree to which malabsorption occurs may vary.

Since the MGB is a relatively new treatment, there is less long-term evidence available about its results and possible issues than there is for the more standard RYGB.

What is the difference between a gastric bypass and a mini bypass?

Gastric bypass, typically referring to the Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB), and the Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB) are both bariatric surgeries designed to aid in weight loss, but they differ in their surgical techniques and some of their outcomes. Here’s a comparison of the two:

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB): In RYGB, the stomach is divided into a small upper pouch and a larger lower pouch. The small intestine is rearranged to form a “Y” shape. The upper stomach pouch is connected to the distal part of the small intestine (the Roux limb). The bypassed stomach and the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum and jejunum) are reconnected further down the intestine to the “Y” junction, allowing bile and pancreatic enzymes to aid digestion.

Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB): The MGB involves creating a long, tubular stomach pouch and then connecting it directly to the middle portion of the small intestine, bypassing the first part of the small intestine. It involves only one anastomosis (connection) as opposed to the two in RYGB.

RYGB: Due to the creation of two anastomoses and rearranging the small intestine in a “Y” configuration, RYGB is generally more complex and time-consuming than MGB.

MGB: It’s technically simpler and generally has a shorter operative time than RYGB.

Both surgeries have demonstrated significant weight loss in patients. Some studies suggest MGB might offer comparable or even slightly superior weight loss in certain scenarios, but more research is needed.

RYGB: Risks include internal hernias, anastomotic leaks, and strictures.

MGB: One of the main concerns with MGB is bile reflux into the stomach, which can increase the risk of ulcers and possibly gastric cancer over time.

Both surgeries lead to some level of malabsorption, which can result in nutrient deficiencies. Patients typically need lifelong supplements.

The extent of malabsorption might differ between the procedures, depending on how much of the small intestine is bypassed.

Both surgeries are technically reversible, but any reversal is a complex procedure. Due to its simpler design, MGB is sometimes considered more “reversible” than RYGB.

RYGB: This procedure has been around for a longer time, so there’s more long-term data available on its outcomes and complications.

MGB: Being a newer procedure, there’s less long-term data compared to RYGB.

How long does a mini gastric bypass last?

When we discuss how long a Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB) “lasts,” we can consider two primary aspects: the durability of the surgical changes themselves and the duration of its effectiveness for weight loss and health improvements.

The changes made to the stomach and intestine during a Mini Gastric Bypass are permanent alterations. However, like any surgery, there could be complications or issues that arise over time which might necessitate a revision or a different surgical intervention. For example, the anastomosis (surgical connection) might require attention, or problems like ulcers or bile reflux might develop.

Most patients experience significant weight loss in the first 12-18 months after MGB, with weight stabilization typically occurring within two years.

Over time, some weight regain is possible, especially if patients don’t adhere to dietary guidelines, exercise recommendations, and other post-surgical lifestyle changes. However, many patients maintain a significant portion of their weight loss for a long time.

In addition to weight loss, many patients see improvements or even resolution of obesity-related health issues like type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and sleep apnea. These health benefits can last as long as the weight loss is maintained, but there’s always a risk of recurrence if significant weight is regained or if other health factors change.

The longevity of the benefits from an MGB (or any bariatric procedure) is strongly influenced by the patient’s commitment to a healthy lifestyle. Regular follow-ups with healthcare professionals, adherence to dietary guidelines, consistent physical activity, and potentially lifelong vitamin and mineral supplementation are crucial to maintain the benefits of the surgery.

Can you eat normally after mini gastric bypass?

Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB) patients must make substantial adjustments to their usual diet after surgery. Because of the adjustments made to your digestive tract, you will have to eat less and process food differently. However, as time goes on, you’ll be able to eat more and more of the things you formerly avoided.

Here’s a high-level look at how your diet will alter and how long those changes will last following MGB:

Immediate Recuperation (First Week or Two)

After surgery, you will only be able to drink clear liquids like water, broth, and sugar-free gelatin.

After a few days, you may be able to transition to complete liquids such protein shakes, milk, yogurt, and broth-based soups without solids.

Three Weeks After Surgery:

Soft and pureed meals will become your new normal as your recovery progresses. Soups that have been blended, fruits and vegetables that have been mashed, and soft protein sources like cottage cheese or scrambled eggs all fall into this category.

One Month After Surgery

Foods that are smewhat firmer than purees will be reintroduced over time. Vegetables, fish, and other delicate meats and fish are examples.

Many Months After the Procedure

After a while, you’ll eat what may be considered a “normal” diet, but in considerably smaller servings. However, even under such conditions, there will be rules and regulations to adhere to.

Due to the limited size of your stomach pouch, you will need to practice portion control. The pain, nausea, and vomiting associated with overeating are all too real.

High-Protein, Low-Sugar Diet: Consume a diet heavy in protein while cutting down on sugary foods and beverages. Some post-bypass patients are more prone to the symptoms of “dumping syndrome” after consuming sugar, which include a high heart rate, flushing, nausea, dizziness, and diarrhea.

Consuming liquids with meals may rapidly fill up the stomach pouch, limiting how much solid food you can eat. Many health experts advise refraining from alcohol consumption 30 minutes before to a meal and waiting 30-60 minutes after eating before drinking again.

Food digestion is helped and obstructed stomachs are avoided when food is chewed thoroughly.

To avoid deficiencies, you may need to take vitamin and mineral supplements for the rest of your life due to the changes in digestion and absorption.

Caffeine and alcohol may both irritate the lining of the stomach, making recovery after surgery more dfficult.

Keep an eye out for intolerances; some individuals, for example, acquire lactose intolerance following surgery.

Can you gain weight after mini gastric bypass?

Yes, it is possible to gain weight after a Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB) or any bariatric surgery. While these procedures significantly aid in initial weight loss by reducing the stomach’s size and altering nutrient absorption, they are not foolproof guarantees against weight regain.

Here are several reasons why someone might gain weight after an MGB:

Dietary Habits: If a person reverts to old eating habits, especially consuming high-calorie, high-fat, or high-sugar foods, it can lead to weight gain. Even with a smaller stomach pouch, consistently consuming calorie-dense foods can add up.

Lack of Physical Activity: A sedentary lifestyle can contribute to weight gain or impede further weight loss. Regular physical activity is essential for maintaining weight loss and overall health.

Stretching of the Stomach Pouch: Over time, if one consistently eats more than the stomach pouch’s capacity, it can stretch, allowing for increased food intake, which can contribute to weight gain.

Maladaptive Eating Habits: Some people develop behaviors such as “grazing” (eating small amounts continuously throughout the day) or consuming calorie-dense liquids (which can pass through the stomach pouch more easily than solids). These habits can result in increased calorie intake.

Alcohol and Caloric Beverages: Consuming beverages that are high in calories or alcohol can contribute to weight gain. Alcohol, in particular, has empty calories and can be absorbed more rapidly after bariatric surgery.

Medical Conditions: Some medical conditions or medications can influence weight. For example, hypothyroidism can slow metabolism and contribute to weight gain. It’s essential to rule out any medical reasons for weight changes.

Mental Health Factors: Emotional or stress-eating, depression, and other psychological factors can influence eating habits and physical activity levels. Addressing these factors is vital for successful long-term weight management.

Not Following Post-Operative Guidelines: Not adhering to the dietary and lifestyle guidelines provided by the bariatric team can impact weight loss results and maintenance.

Is the stomach removed in mini gastric bypass?

The stomach is not bypassed during Mini Gastric Bypass (MGB) surgery. Instead, this method entails the following steps:

A long, tubular stomach pouch is created by separating the upper part of the stomach from the remainder of the abdomen. The pouch is much smaller than the patient’s original stomach, limiting the quantity of food that may be consumed at one sitting.

The newly formed stomach pouch is attached straight to the middle section of the small intestine, skipping through the first section of the small intestine (consisting of the duodenum and a section of the jejunum). As a result of the bypass, fewer calories and nutrients are absorbed.

The greater section of stomach that was skipped is still there in the body, but it is no longer used for digestion. However, the stomach keeps secreting acid and digesting enzymes, which eventually combine with food in the small intestine.